Crossing the Lines: In Pursuit of (Linear) Freedom, Part 1

Linear Modalities

And what about the linear conception? What about those musics of the world that feature one rhythmic line, with or without a highly inflected feel? Perhaps the most complex, most complete rhythmic system in the world comes to us from India, as we have already seen. But rhythmically intricate though it is, Indian music is delivered linearly. Does the harmonic perspective of rhythm apply? The (hypothetical) answer is yes. In Toro’s words, “Indian music is a linear delivery of a harmonic approach.” (Toro 2011c)

I had known this for a long time already, in some sense. Through classes, conversations with other musicians and my own listening experiences, I knew Indian music to be fast, intricate, full of ‘odd’ metres and long phrases that cross the metric structure. I also knew African music used only some of the vast rhythmic palette of India but with a difference: In Africa it happened at the same time.

But, before embarking on this study I was not thinking about the harmonic series, or about the relationships between all the various dimensions tapped by Indian music. Indian music, with respect to the various metric schemes explored by the tala system, is in touch with the harmonic conception of rhythm, even if the different metres are not rendered simultaneously. What is more, if we consider that the tala, which is usually rendered by the ostinato of a non-solo instrument, and/or counted with hand claps, finger taps and waves by the audience or other performers, forms the metric backdrop against which so many variations and metric modulations are performed, then, in a sense, this music is also rhythmically harmonic.

But the purpose of this discussion is not to discuss Indian music on its own, it is rather to investigate some of the ways in which the harmonic perspective of rhythm might inform the linear concept of musicians from any tradition.

Three Steps to Freedom

Toro said on many, many occasions that his method and message is simple and that it is all based on downbeat, upbeat, and dotted note. According to him, these three things allow one to ‘play.’ By play, he means to feel free and to make phrases which may or may not agree with the metric structure but never to be lost, or to lose connection with that structure. To qualify his statement, I might phrase it thus: Within a certain metre, a solid grounding in downbeats, upbeats and dotted notes allows a musician to be rhythmically adventurous without guessing. Incidentally, the harmonic relationship of two and three and their ‘octave’ derivatives are also to be reckoned with in this approach. But how does this work?

The Power of Motion

At the foundation of the approach is motion. According to Toro, a musical motion is comprised of complementary down and up phases. By playing this way, working with gravity, the musician benefits by: using less effort to get a bigger sound; playing faster by getting two or more articulations per stroke; producing a more musical sound, that is, more intentional and more ‘natural’, being comprised of complementary elements, and sounding like a body in motion, rather than a machine or computer[1]. The conscious development of this approach also facilitates the parallel development of awareness—of bodily sensations, of sound, of being connected to or engaged in the process of playing an instrument, etc. While discussing these concepts with Toro, I mentioned some lessons with my old composition teacher, Dr. Paul Renan, himself an excellent pianist and advocate of the Alexander Technique. (Renan 2002) I had related Renan’s words about feeling an internal circular motion in the arms while playing:

ET: Of course. It’s the motion. Only a few people know about that. All the other ones are stuck, and they have no clue. It is the basis. Because when you do this it releases. It releases the energy, and stress.

JD: Like Tai Chi.

ET: Well yeah it is Tai Chi. Everyone that discovers this in different parts of the world calls it whatever they want. And it’s the same idea of Joseph Campbell and Jung of the basic and the cultural. The basic is this motion. Mechanical. Correct mechanical motions. And if its discovered in some…place they call it…call it whatever you want. It’s just the right motion.

JD: Moeller, Alexander…

ET: It’s just the right motion. Look at how a wave does. Just look at the ocean. It’s what happens. Some humans are hip to things. Some humans are not. I could be hip to a musical idea. I might not be hip to some other idea. It doesn’t mean that because you’re sensitive to music you’re sensitive to everything else. People can walk. I’ve taught people who have no musical ability, and they can’t play in time, but they want to play a drum. What do you do? Well, I say to that person, ‘Walk.’ See people walking. You can walk in time. People walk in time. If you didn’t walk in time, you’d be out of breath. So, think of your walking. And play with just the same timing, as you do your walking. It’s a great connection. You walk. If you can walk, you can play! That you are disconnected from that event, I understand. But think of it, clearly. Put it in your conscious mind, of walking in time. And play…with the same idea…

JD: So you can play almost any speed without getting tired?

ET: That’s the idea. But the main idea is that it produces a musical motion. The other one doesn’t produce a musical motion, because musical motion comes from the irregular or oval cycle.

JD: Yeah. It’s like there’s a resting phase and then almost a point.

ET: There’s gravity and no gravity. (Repeats) And that’s a downbeat and the offbeat. If the offbeat had gravity it would be an on-beat. (JD laughs) Of course. The offbeat doesn’t have gravity. An orbit doesn’t have gravity until those points, and then it does this kinda stuff (snaps hand downward).

JD: It accelerates away and then gravity grabs it and says, ‘come back.’

ET: That’s right. And that’s the truth of nature. But we can avoid that like this. (Plays stiffly with pointed finger— Downbeat, downbeat, downbeat, without upbeats.) (Toro 2012a)

He also draws analogies to other human endeavours, such as throwing or hitting a ball, and touches on the need not only to produce a natural motion, but to surrender to that motion, as a surfer to the wave. In a sense, from this perspective, the correct motion is not ‘produced’, it already is.

ET: The idea of the downbeat and the offbeat, it’s what creates music. So that motion is important if you’re playing an instrument for musical purposes. Otherwise, I think it’s the right motion because it’s the right motion you can see. When you walk or when you throw a ball correctly or whatever…it’s the motion of a wave. It just makes sense.

JD: No wonder you like surfing…to be with the waves.

ET: Yeah, it’s really interesting if you can get hip enough to be with the wave to see how it moves. If you’ve seen in my videos of surfing, I go with the wave. It’s difficult as sometimes you want to carve the wave. If it’s not good it throws you off, like a horse or something. But when you can feel the contour and where the wave wants to go, it’s an amazing feeling…just like music. So I realized many, many years ago that music is a monster that develops and if you’re sensitive to it you let the music carry you. When you do that then you’re at a different level of playing. So the music dictates what you should play. So there’s this motion. Once you get the motion, it becomes effortless. The Hindus have discovered that. (Demonstrates, dropping hands in front) (Toro 2012a)

Toro’s method advocates the consistent development and reinforcement of this correct down-up motion, in the weak hand, while adding other motions in another limb, in gradually more difficult relationships. This is the approach in his book, For Your Hands Only.

So the basis of what I’m talking about is in that book, For Your Hands Only. That is a book for anyone. For any instrumentalist. It has nothing to do with percussion. Except it’s written in the language of a conga drum. Its just the most accessible thing. You can do it on your lap. So it’s the idea of becoming aware of the downbeat and the offbeat feel. And being able to feel that within you.

So, without losing the feeling for the downbeat, you accent the offbeat. See? It has a different effect. And then, all of them. And then in between. What I’m trying to accomplish with this is to get a feeling of the pulse. Getting a really grounded feeling of the pulse without using your strong hand to do that, but using your weak side to have that feeling of ground. Your weak side. And that kind of balances you out from this (shows one hand forward like drummer’s ride) to this (puts both hands out). So that’s the whole idea…and then the dotted notes. And when I did that I noticed that if I didn’t count I would get lost. And I asked myself why. Because every time it goes to the offbeat and comes back to the downbeat, it seems like one. And it’s not one. It takes three patterns to get to one. (Toro 2012a)

The beginning of that book then, shows an ostinato like this. Note the down and up, as indicated by note height:

Over which these other motions are practiced:

Figures 1 and 2. For Your Hands Only First Exercises.

Audio Example 1. For Your Hands Only, First Exercise (CD Track 37).

Motion in Another Tempo: The Dotted Note

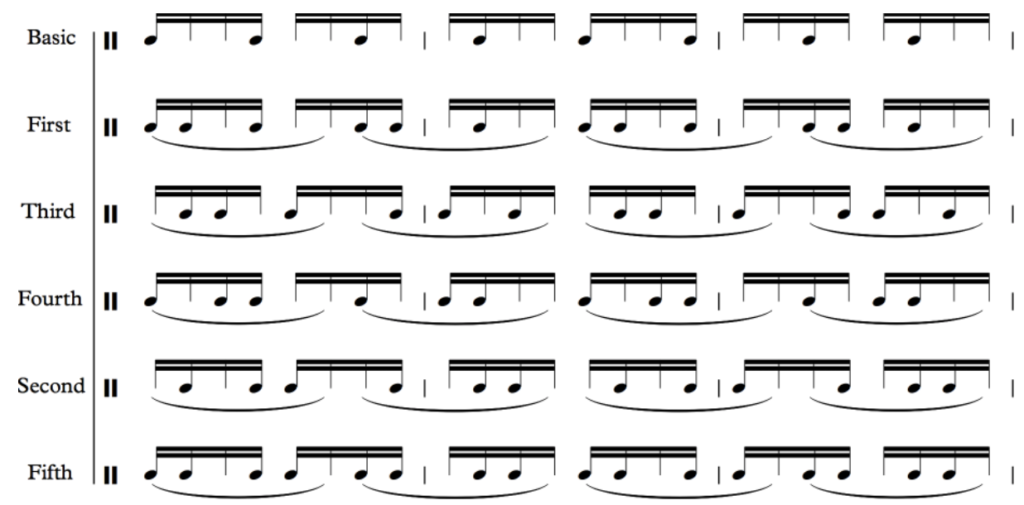

As suggested above, each line/combination deserves significant, engaged repetition, with the aim of developing and deepening the grounded, motional concept. Toro then gives his six basic versions of the dotted note, which are combined with the same ostinato:

Figure 3. The Dotted Note Applications.

I have listed them in the order I am accustomed to practicing and remembering them, labelled in Toro’s way[2]. Here is the same with all subdivisions indicated:

Figure 4. The Dotted Notes with All Subdivisions Indicated.

Audio Example 2. For Your Hands Only, Eighth Notes with Groups of Three (CD Track 38).

Though I have practiced these ideas for many hours and find them to greatly enhance my concept and playing, I still struggle with all-encompassing pronouncements, such as, ‘That’s all there is,’ or, ‘Everything you’ll ever play is that.’ Greatly impressed by Toro’s abilities and commitment to his version of the nature of rhythm, however, I feel compelled to explain the paramount importance this material may hold for the development of a new type of musicianship. This explanation is an important intention of this thesis.

A New Vision

At the foundation of the envisioned perspective on rhythm, I see three fundamental characteristics: 1) The capacity for one person to present a highly multi-dimensional rhythmic framework, as is normally heard in various, especially African Diaspora AT/Music traditions; 2) The capacity to also play complex, linear combinations, in the manner of especially Indian Classical music; 3) To work at this level with a high degree of analytical, conscious understanding of what one is doing, hence the ability to always vary the possibilities, not only play from one’s tradition. Toro often referred to doing ‘rhythm,’ (from/open to all that is possible) as opposed to ‘music,’ (from certain traditions) and I believe this summary approximates his intention:

And so, the Hindus have thought of rhythm in a fundamental way. They’ve studied this stuff, and…but their interpretation of it is linear. You see? Where the Africans’ is harmonic. And so why not mix both? And the Hindus, you know, Swapan (Swapan Chaudhauri, tabla guru, who gave Toro several tabla lessons) didn’t want to hear about that. And so, it’s that kind of stuff. The mixture of both is best! Really, to be able to…and in tablas, I can do both things. I can do this linear thing, and I can do this harmonic thing. This is the next step. But, you know, this idea, it’s beyond intuitive because this (the harmonic series) is intuition. And the Hindus, not intuition! It’s learning. And the combination of both philosophies is the best! One is not better than the other. Those together is the best. You know? And so we’re missing that. We’re missing that completely, and that’s where I’m at. This (the downbeats, upbeats, and dotted note) is a Hindu idea, on a harmonic basis. And I saw that. I saw that immediately. It’s quite simple. Downbeat and upbeat and dotted note. It (dotted note) doesn’t exist, but here (two and three in harmonic series), this is the same thing! (Toro 2012n)

Most people just copy one dimensional patterns. Or they get it but don’t understand. In the modern world, you need both. You need to do it and you need to understand what it is. (Toro 2012h)

At

the foundation of that foundation, then, are skills that, in Toro’s view, are best

developed through something like the aforementioned method. If the downbeat and

upbeat are absolutely solid, grounded and thoroughly assimilated in the

player’s body, the next step is something that challenges and therefore

strengthens that centred-ness. The first series of exercises goes ‘against’ and

all around the downbeat at the beat-specific level. The next series, those

involving the dotted note, do so at a cycle-specific level, or rather, the

level of several cycles. To fully digest the dotted note involves going ‘in’ to

it and being able to ‘look’ back at the downbeat/upbeat cycle, and vice versa. This

is the foundational exercise for developing a multi-dimensional awareness. But

why the dotted note specifically?

Continue to Part 2…

[1] Whether computers and machines are ‘musical’ is another discussion. Assuming that music is a human phenomenon, is it not the human-ness with which the machines are directed that makes noise into music? I do not wish to draw the wrath of any computer music advocates, but I have left the statement as is under the assumption we are talking about instruments where a significant component of the sound production and micro-rhythmic placement is generated by human movement.

[2] Toro seems to order them according to the first position of the double articulation, i.e.: 1) from the downbeat; 2) to the downbeat; 3) to the offbeat; 4) from the offbeat; 5) all combinations in succession. I prefer to think of them as: double-single starting from the downbeat; double-single starting after the downbeat; single-double starting on the downbeat; single-double starting after the downbeat; double-double with a space between. Each combination cycles through several positions with regard to the sixteenth note, 2/4 cycle, so names are a personal preference.

Bibliography